‘It’s a crisis – a much harder to measure crisis’

Water. A luxury that most of us take for granted. This is something that I have come to terms with as a practising Muslim through the yearly fasts I undertake. Every year, once a month, Muslims fast for approximately 12-18 hours a day and this means that we cannot drink any water, nor eat anything until sunset. My friends applaud me in this act of strength and resilience and I myself feel proud that I can go 18 hours without water. However, during the month of Ramadan, I came to a deep and profound understanding of the reality in which some people live. Allow me to provide you with a glimpse of how millions of people live.

- 1 in 3 people across the world do not have access to safe drinking water, which makes up almost 2.2 billion people globally (UNICEF 2019).

- The majority of Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) is facing economic water scarcity due to a lack of infrastructural networks to provide Africans with access to safe water, rather than limited availability (Gaye and Tindimugaya 2019; Rijsberman 2006).

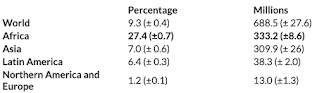

- 333.2 million people across Africa are suffering food insecurity with alarming rates of increase in SSA as shown in figure 1 (WorldHunger 2018).

Figure 1- Percentage and number of people affected by food insecurity in 2016 (FAO 2018).

As an introduction to this blog, it only feels right if I try to voice some of the concerns that Africans are facing today, as a starting point to exploring the complexity of water and food scarcity across this continent.

To understand water scarcity, it would be a good idea to start with metrics of water scarcity. Falkenmark et al (1989) described water scarcity through the Water Stress Index (WSI), stating that a country is considered ‘water scarce’ when the available renewable water is below 1,700m3 per capita, per year. Unfortunately, it is much more complex than this. This metric fails to consider the socio-economic and political factors, which are foundational in providing a holistic image on water scarcity in Africa. It fails to account for economic water scarcity and focuses predominantly on physical water scarcity. Some countries have insufficient funds to put in place adequate infrastructures to access clean water (Damkjaer and Taylor 2017). Furthermore, a country may be sitting on a transboundary water source that is being heavily disputed, affecting citizen’s access to water. Finally, it would be inappropriate to apply the WSI index across all countries and regions because there are geographical variations in both availability and access to water (Gardner-Outlaw and Engelman 1997), which would be committing fallacy of composition.

It is important to note that these critiques are shining attention on the idea that water scarcity is unrelated to accessing safe water (Damkjaer and Taylor 2017). Consequently, greater focus needs to be placed upon accessing safe water rather than availability. The MacDonald et al (2012) emphasised that some countries in Africa are sitting on vast volumes of productive aquifers (figure 2) but they do not have the means to access the resource. If Africans could obtain the water, the effects of food insecurity would be greatly minimised.

Figure 2 – Aquifer productivity across Africa (Bonsor and MacDonald 2011).

A primary concern for millions of Africans is food security, which has been disrupted for reasons such as population explosion and climate change; these are issues I aim to learn more about throughout this blog series. To shed some light on this issue, I will start by briefly explaining the complexity of food insecurity in Africa. Climate change has meant that Africa is facing more extreme weather conditions, from droughts through to intensive floods. This volatility of climate change has affected irrigation and food production in Africa, which has caused a decline in food production per capita, resulting in 56 million physically stunted children across SSA (Funk and Brown 2009; Gates 2014). This is just a small insight into this tragedy that millions of Africans face and I, alongside those who are reading, hope to gain a greater understanding on this issue that has persisted throughout time and space.

My knowledge on this issue is limited but I am looking forward to gaining an understanding of this issue that Africans are forced to deal with. I aim to look at the relationship between water and food, the political, economic and environmental factors affecting the two, exploring the notion of virtual water and much more. By exploring the complexities of water and food systems across Africa, I aim to discover other important themes and issues. These will be distinct but interconnected to water and food issues.

Thanks for reading, stay tuned!

I really like how you have started by shining a light on the importance of water and why it is necessary to focus on water scarcity. Using your own insights are also great as it makes for a very compelling post. Continue to synthesise and reference material in the way you have done here.

ReplyDeleteWhile I think there is a lot of value illuminating the many interconnected issues around water and food such as water security and climate change, it may complicate your text. Perhaps include a sentence or two to make it clear that by exploring water and food you will be illuminating a range of other secondary, but interconnected issues. You will explore these in separate blog posts.

Perhaps consider increasing the font size of your blog? It will improve its readability.

(GEOG0036 PGTA)

Thank you for your feedback! I hope you continue to enjoy the future posts.

ReplyDelete