Virtual water – a solution to food scarcity?

Have you ever considered how much water is needed to produce food? When I found out that around 3.8 trillion cubic metres of water is used by humans annually, most of which is used for the global agriculture sector (The Guardian), I felt confused. If there is this much water to produce food, how is there a water shortage around the world, in places such as California and Libya? This is where virtual water comes into play as it makes a connection between water and food. I have learnt that virtual water, a term coined by Allan (2003), is ‘all water used in a commodity’s value-added chain, including water crossing borders as a result of trade in water intensive goods’ (Gawel 2012: 168). In essence, virtual water is the water that is embedded in food and agriculture, which can be better understood as ‘invisible water’. Seems pretty straightforward right? Unfortunately, not… I aim to evaluate the usefulness of virtual water as a concept to help manage water scarcity issues across Africa.

To help our understanding, let’s consider the following example of Egypt:

- Africa is importing $35 billion in food annually because they do not have enough water to provide sustenance (Africa News); this links to El Sadek (El Sadek 2010) idea that an indicator of a water shortage is the level of food imports.

- For example, Egypt is classified as a water scarce country and heavily rely on food imports to feed its population, as the FAO highlighted that Egypt imports have exceeded US$3 billion in recent years

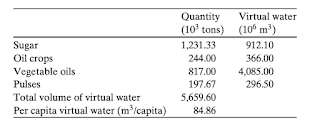

- The food listed in figure one is products that Egypt are importing, which are water-intensive goods.

- Some scholars argue that water stress can be relieved through water imports (Islam et al 2007), and this management idea has been adopted by Egypt.

Figure 1 – ‘Volumes of virtual water embedded in the net imports of non-cereal agricultural food products in Egypt’ Yang and Zehnder (2002).

You may be wondering how does this help with water and food scarcity across Africa? Powerful individuals and organisations who manage water and food resources can be more strategic with consumption, by importing water-intensive goods, resulting in a greater volume of water for industrial and domestic uses (Lillywhite 2010). Despite this, some scholars argue that virtual water simplifies water to a purely agricultural matter (Barnes 2013); there are other issues at hand, such as a lack of sanitation and a gendered divide in access to water. However, conceptualising virtual water will encourage municipal governments to import water-intensive food, which means there is a greater allocation of water to other sectors. This will aid the strategic governance of water management and give light to the consideration of water on a more global scale (Hoekstra and Chapagain 2008). I would therefore argue that municipal governments should spend more time implementing policies with a greater focus on food importation rather than on the investment in the domestic agricultural sector.

I have explored some critiques in order to comprehend the complex nature of water and food, and how virtual water acts as a partial means of understanding water scarcity across Africa. Some economists have argued that virtual water lacks validity in policy making (Antonelli 2014), thus it is difficult to make decisions on access and availability to water based on this notion. However, I argue that by acknowledging the fact that food has a high-water footprint, it can help to consider the way in which water is distributed. This is supported by Yang and Zehnder (2008) who contend that virtual water is crucial to managing water resources and can be incorporated into multidisciplinary assessments of water allocation.

I believe that virtual water would be better understood in relation to water footprint as the concept in isolation is misleading; virtual water is not an actual commodity (Merrett 2008). I was naïve to believe that virtual water could help to solve water and food scarcity across Africa, but having investigated the notion, I can see that it has potential to help governments and communities better distribute their water resources. Nevertheless, some African countries are facing a physical lack of water and virtual water does not address this issue; it is not as simple as transporting containers of water between countries. Moreover, not all countries can afford to import food and thus, they must seek water supplies to provide affordable food for its population. In my next blog post, I aim to explore groundwater stores and technological measures that help to gain access to ‘real’ water.

For more information, have a watch of this TED talk!

Hey Thaneya! This is a brilliant post and I think the way you’ve discussed incorporating the idea of virtual water into policy is really interesting. As the world becomes more water scarce, are there risks involved in using the term virtual water to justify relying on food imports?

ReplyDelete