The hidden potential of groundwater

Having read Sauramba’s piece on groundwater resource, he proposed that the solution to water scarcity across Africa can be found beneath our feet: groundwater aquifers. I was never quite aware of the extensive supply of water that was hidden from us. Sauramba opened my eyes to the possibility that groundwater could help millions of Africans with their water and food scarcity problem. If groundwater is used and managed sustainably, it can provide safe water for approximately 40% of the South Africans. However, the complexities of abstracting groundwater supplies must be considered as there are huge barriers standing between access to the groundwater and the actual supply of water. Therefore, I endeavour to explore the possibilities of groundwater being a saviour to water scarcity across Africa, with specific focus on how it can help with food insecurity. Nonetheless, I will be challenging this solution as I believe that extracting groundwater will require years of planning, understanding and negotiations.

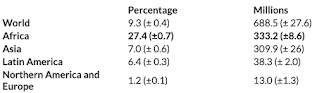

So, how much groundwater is there and is there enough to irrigate agriculture? Giordano (2006) approximated that total groundwater-irrigated area in SSA to be 1-2 million ha, illustrating the potential to increase food production across SSA. This will support the growing population and provide a sustainable livelihood for smallholder farmers as they are able to move away from subsistence farming, towards a market-orientated farming approach (Dittoh et al 2013). Figures one and two display the optimism towards groundwater supplies across Africa. These maps show that there is a widespread variation in groundwater resources across Africa, supporting the development of handpumps and boreholes. However, the validity of this data is to be questioned as regions such as Central Africa lack quality hydrological data. It is important to explore this topic in more detail so that a well-designed solution can be developed.

Figure 1 – A map to illustrate aquifer productivity across Africa.

Figure 2 – A map to illustrate the saturated thickness of aquifers across Africa.

Nonetheless, studies have shown that some countries across SSA have the potential for groundwater irrigation, a total of 13 million ha, delivering to 26 million smallholder farmers (Pavelic et al 2013). A success story of groundwater irrigation is seen in Ghana where farmers who utilised the groundwater received a 20% higher net revenue per irrigated area compared to those areas that use surface water (Dittoh et al 2013). This illuminates the prospect of a hidden supply across Africa and with successful management and knowledge on groundwater resources, this could be part of the solution to the big problem of food and water scarcity.

We should be optimistic about the potential use of groundwater supplies but there are challenges which need to be addressed. There is an abundance of obstacle that I came across, but I want to explore an interesting challenge that I discovered. I came to learn about the impact of groundwater irrigation on women; I was unaware that it would impact men and women differently. Women are disadvantaged due to the lack of land tenure (Torou et al 2013); consequently, they were unable to access a loan, which would have been used for irrigation equipment. Furthermore, inevitably the biggest barrier is finance. Most countries across SSA do not have the money to invest in groundwater (Villholth 2013), which means they tend to neglect it, but this opens up the opportunity to private investment. This will be explored in the next blog post.

Nevertheless, groundwater is resilient to climate change which is why I conclude that this is the potential panacea to water scarcity across Africa. However, this is heavily dependent upon management, knowledge and governance of resources. Climate change has meant that groundwater stores can be replenished at a greater rate, thanks to heavy rainfall events such as El Niño (UCL 2019). But climate change and its implication on groundwater needs to be analysed further in order to create an effective adaption strategy.

In my opinion, groundwater supplies can be a sustainable solution to managing food and water scarcity, providing that there is an understanding of the complexities and challenges of the source. Long term planning is essential due to the nature of recharge. But it is important to remember that the exploitation of groundwater is context sensitive, denoting that this solution cannot be applied across all regions as there are socio-economic, environmental and political variation between each area.

Is privatisation the solution to enable access to safe water? In my next blog post, I hope to explore the governance of water supplies and who should be responsible for supplies: the private sector, government or community?

Detailed analysis of the current and possible future role of groundwater that does really well to highlight its limitations. You could maybe have also touched on water quality, which is another significant issue in Africa, mentioning for example how the movement of groundwater through soil can help disinfect the water and improve its quality.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your feedback Andrei! Water quality is a very complex and interesting issue which I will have a look into.

Delete